How I Founded The [Represent]atoire Project

In 2019, I had the incredible privilege of performing John Corigliano’s Grammy-award winning First Symphony during New York City’s WorldPride and 50th anniversary celebration of Stonewall with the Chelsea Symphony. The celebration was the largest LGBTQIA+ event in history and marked the first time WorldPride had been held in the US.

Clarinet Section for Symphony 1 with John Corigliano

at the DiMenna Center for Classical Music in NYC

The First Symphony premiered in 1990, the year I was born, at the height of the AIDS crisis. Inspired by the AIDS Memorial Quilt, the work commemorates Corigliano’s friends he had lost, and was losing, to the disease. This is a history that you can’t find in a book. Performing this work with Corigliano front row in the audience and having the opportunity to talk with him about his music (especially the Clarinet Concerto, one of my favorite pieces to perform) is an experience I will remember for the rest of my life. The Eb clarinet part that I played represents gay rage, and undoubtedly, I am still processing my own. But it wasn’t until I started my current position as Assistant Professor of Music and coordinator of woodwinds at Coastal Carolina University in August of 2020 that I really was forced to process how meaningful this experience was for me as an openly queer person and how formative it would be for my teaching going forward.

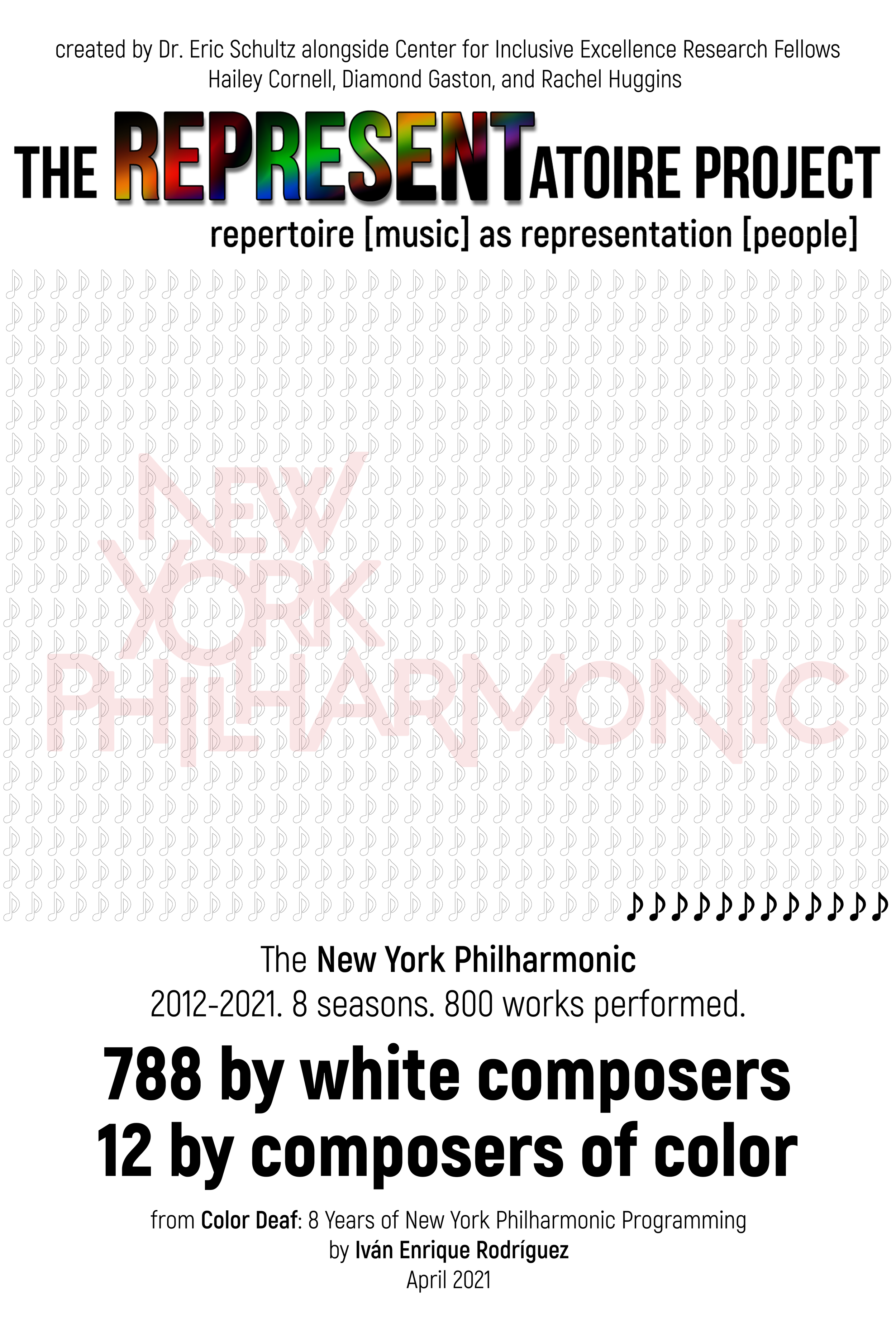

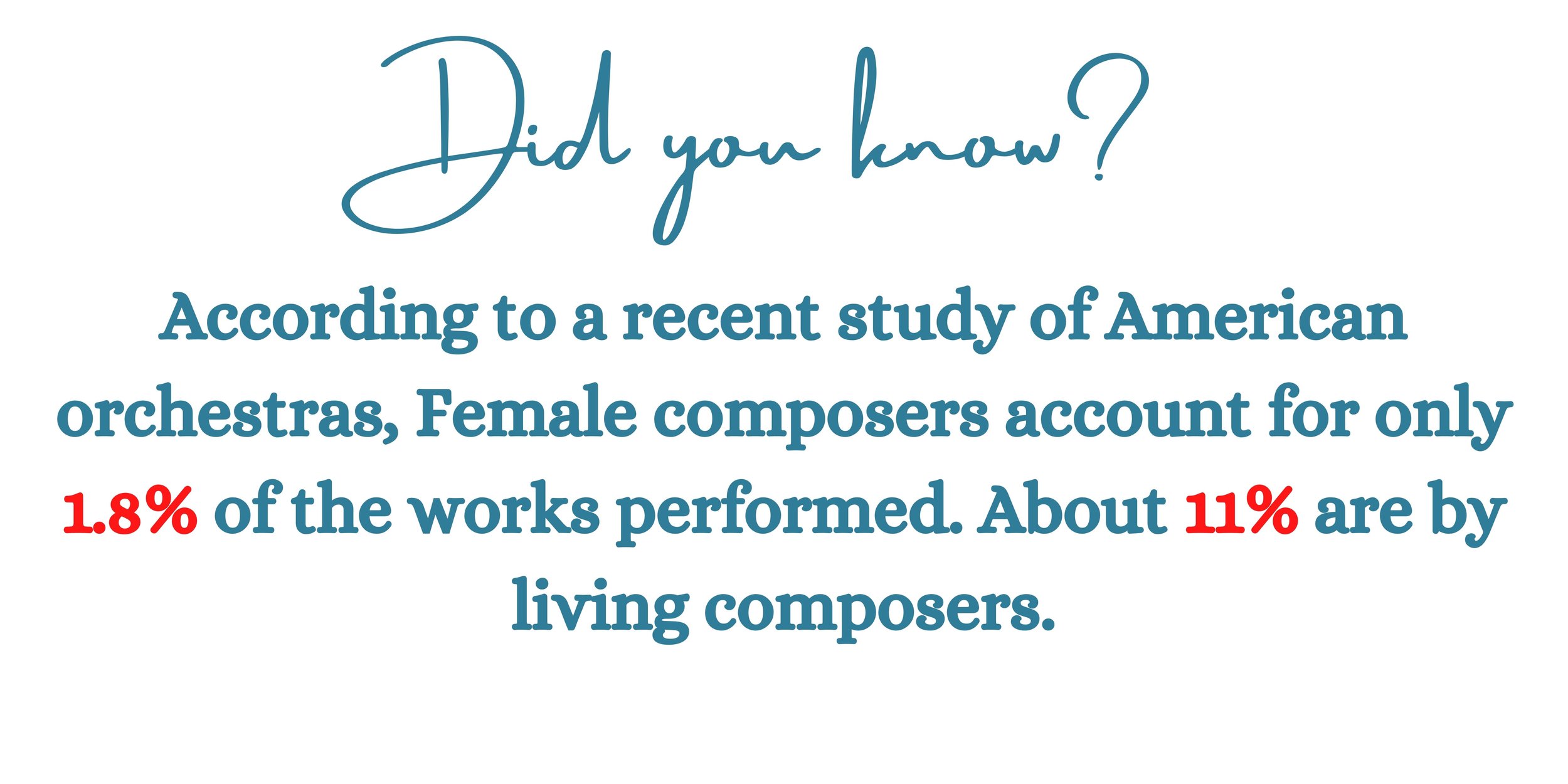

Traditionally, during an undergraduate music degree, students study and perform the standard repertoire for their instruments. Certain composers are so monumental (Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms) they really cannot be ignored. However, the canon reflects historical marginalization of certain groups and communities. For example, there is no commonly performed undergraduate repertoire for the clarinet written by a woman. Even with a terminal degree in the field, I struggle to think of a standard undergraduate piece by a BIPOC composer for any woodwind instrument. There is no excuse for this. A repertoire list from the past may reflect some of the greatest music ever written, but it also reflects our biases as a society. It reflects who we thought could write great music, and from where great composers could come.

My approach to diverse repertoire, particularly music by living composers, is markedly different than the prevailing approach today. I believe that we need to approach new repertoire with the same level of veneration that we give to the music of Mozart, Tchaikovsky, Brahms, and Beethoven. When we study these composers, it is from every possible angle – theory, historical context, appreciation, applied performance, historical performance practice, personal lives, written letters, and more. Living composers simply do not get this level of commitment.

To remedy this, over the last two years we have focused our efforts on two living composers, selected in conversation with my students. When we discovered Amanda Harberg’s Clarinet Sonata, it became clear that my studio wanted to study this composer further, and her music has now taken over my studio, from her woodwind ensemble works, to her new piccolo solo, to her powerful, meditative Prayer.

Students, faculty, and community members have shared incredibly vulnerable and personal stories with me because of this project. One student of mine, a Black female flute student, shared with me that her former teacher had mentioned her lips were too big and she would never be able to get a “classical sound” out of the instrument. She told me that when she was a little girl, she searched on google images for someone who looked like her playing the flute. Finding Valerie Coleman was the reassurance she needed to persevere. This story made it clear to me that we needed to seriously study the cannon of Coleman and Imani Winds.

But we didn’t simply study a few pieces of music to check a box and move on; instead, I launched a yearslong education campaign on these composers – their backgrounds, their struggles, their theories, the stories behind their music. For example, we recently interviewed Amanda Harberg. Because we had studied her music at length this year and understood who she was, the students were excited about this project and thought of meaningful questions they wanted to ask. We studied the art of interviewing. In the Center for Inclusive Excellence where I serve as director, we read many interviews that Valerie Coleman has given over her career to understand where she comes from. She talks proudly of her hometown, the west end of Louisville, and mentions frequently that it is the same neighborhood that Muhammad Ali grew up in. She complicates this by reminding us that this is also the same neighborhood in which Breonna Taylor was murdered.

In my woodwind ensemble, I took significant effort to arrange Coleman’s landmark work, Umoja (Swahili for unity), for our full instrumentation. This took hours of arranging, but it was worth it, because I believe that anyone who wants to be a part of this movement should have that opportunity. The students love Umoja – not just because it is a great piece, but because they understand the story behind it. Coleman made history in 2019 when she became the first living Black woman composer ever commissioned by the Philadelphia Orchestra (a “Big Five” American orchestra).

One day I asked my Woodwind Ensemble, “For how many of you is Umoja the first work you have performed written by a Black woman?” The impact of every hand in the hall going up was one of the most overwhelming moments of my entire teaching career. When my clarinet student Hailey discovered the composer Amanda Harberg and learned her Clarinet Sonata, this was the first time they had ever played music by a woman composer. These are college music students with over a decade of music study.

Of course, accessibility of new music can be a concern for students. It is not freely available online like much of our repertoire in the public domain. When I acquired Valerie Coleman’s entire music library here at Coastal Carolina University through grant funding, the students couldn’t wait to get their hands on her music and see what pieces they may want to study next – and we now have the largest collection of her music anywhere in the world at Coastal Carolina University. My flute student Diamond’s senior recital featured several works from the Coleman Music Library, and she made history at my institution by performing the first ever student degree recital to feature all women composers. Shortly thereafter, Hailey became the second.

When I announced to my studio that I had secured Valerie Coleman for a residency here at CCU, the students were ecstatic, because they actually had the context and education to understand why that was significant.

Our project has been the subject of many articles and local TV features this past year. One question that I was asked in an interview, “How did you come up with such a clean, cohesive way to approach this project?” caught me off guard, because I never saw it that way. The truth is this project was born out of conversations with my students. It happened organically. To be sure, I have guided the students, but they also see the urgent need for this work and are excited to contribute. Importantly however, this question forced me to think about how to make this project sustainable, and how it could be replicated around the country.

Last year, I coined the phrase and announced our new initiative, The [Represent]atoire Project (musical repertoire, or the music we traditionally perform, as representation). Every year, I will select one or two living composers to focus our study on for the year. The benefit of this approach is that it will allow our students to focus deeply on these composers, in a manner more comparable to how we seriously study the classical titans.

An unexpected reward of this project has been the amount of support and excitement surrounding it. Students want to be involved in this project and I am proud of the supportive and inclusive environment we have created in this ensemble. Motivating to the students, our social media accounts frequently engage with these composers and other renown artists and composers around the world. Valerie Coleman often cheers our students on when they approach a new piece of hers. Living composers like Amanda Harberg are thrilled to do an interview about their music. This kind of networking possible through social media and technology puts our students on a new global stage and is something that traditional collegiate music education has missed out on in the past. In this sense, it is revolutionary.

But it’s so much deeper than that. This matters. When Hailey performed the Clarinet Sonata in a recital featuring Harberg’s music that they organized, I have never heard them sound better. There is a connection they had to this piece that they just didn’t have with the Mozart Concerto in the fall, and that’s ok. They care so much about this music, and you could hear that come through in their performance. When Diamond performed Harberg’s Prayer, from memory no less, several in the audience shed tears because of her beautiful playing, and because we knew the story behind the work. I was one of them.

As an openly queer person, I know what it feels like to be marginalized. Born into the height of the AIDS crisis, and coming of age pre-Obama, never in my wildest dreams did I think I would ever be able to be completely out, and certainly not in a university setting with my students as a faculty member. We have a long way to go, but things have changed quickly in this country for LGBTQIA+ rights. I know firsthand that it is the most liberating feeling in the world to be yourself, and more than anything, this is what I wish for the next generation – no matter who you are, where you come from, or what you have been through. This is what I strive to teach my students.

As artists, we have access to the most powerful form of magic, the ability to create something out of nothing.

I believe music is the most capable tool we have, and it is an unlimited resource. Let us use it so that:

Maybe one day, it would be unimaginable for an unknowing band kid to go a decade without playing one piece of music by a composer from their own community, whatever that may be.

Maybe one day, a Hispanic student won’t be shocked when music handed to them shows that a renown composer has their same family name.

Maybe one day, a little Black girl will not have to search through google images to find someone that looks like her playing the flute.

It is my sincerest hope that music teachers, institutions, and presenters around the country will take the idea of this project and replicate it.

The time is now.